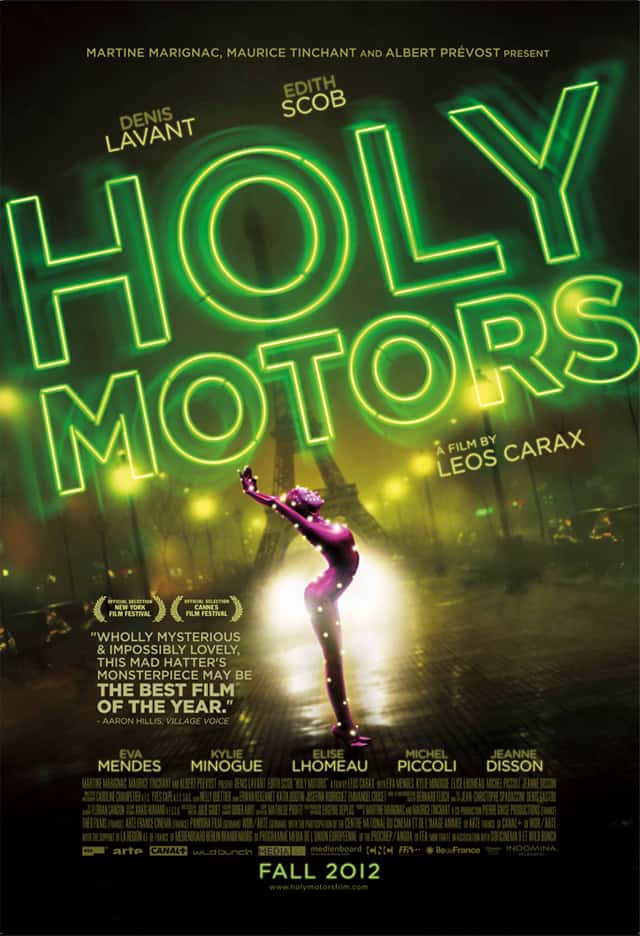

FF ’12 Review: ‘HOLY MOTORS’

“Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind could invent.” That memorable quote from Arthur Conan Doyle has always stuck with me and came to me on several occasions while watching Leos Carax‘s film Holy Motors. Depending on how you view this bizarre and frequently absurd French film, the quote from the creator of Sherlock Holmes can be applied to this new film in multiple ways. Motors is without a doubt a strange film that aims to push the viewer to question the role in which the arts, identity, and society affects our lives and how our mind perceives these facets of reality. How strange, indeed.

On the surface, Holy Motors shows the daily routine of one man as he makes his way across Paris in his limousine which takes him from one “job” to another. This man who takes on the role of several characters – both male and female – over the course of 24 hours literally steps into the shoes of these “people.” The back of the limo serves as a dressing room of sorts complete with a make-up station, wigs, costumes, and prosthetics in order to play the parts. What follows is a series of performances and vignettes that are just as bizarre and quirky as they are touching and thought provoking.

There’s only so many ways that I can drive home the point that this film is just as much about the viewer and his or her’s acceptance to pull back the film’s many layers. It’s not a stretch to say that film classes could spend days or even weeks analyzing the meanings of such sound cues and specific words strewn through the segments; I wouldn’t be surprised if this does happen in the years following the film’s release. Without getting too metaphorical just yet, if you look at the film purely on a formalistic level, Carax continues his reputation as a leader in arthouse cinema. His eye for striking compositions and dramatic lighting is accompanied with memorable operatic compositions that are simply a joy to watch unfold. The performances Carax pulls out of his actors feel both completely grounded in this alternate reality of French society while still maintaining a feeling of apprehension over what will happen next; the audience also feels this unsettling feeling of where this rabbit hole of a film is going to empty them. Star Denis Lavant literally has to carry the weight of the film on his back since he’s in almost every second of the film, and it’s not an overstatement to say he gives the best performance of the year. Watching him light up the screen with a new persona every ten to fifteen minutes is a spectacle to see. Effortless doesn’t begin to describe the way he tackles each distinct character.

Most of the “characters” Lavant performs as feel more like vessels to exhibit the philosophical ideas of the film. So to say they are characters might be a stretch even though they still convey a level of humanity. No, it is not necessarily the point for you to sympathize with these roles, like the father picking his daughter up from a party or the elderly man dying in bed with his daughter at his side, but to see them as a reflection of the roles we have to play in our lives and the many hats we wear to appease others in our daily life. Oscar doesn’t necessarily care about these jobs when he’s preparing in the limo, but he conveys the feeling that they must be done. And it’s when he interacts with outside individuals as these characters that we see him come to life. It’s as if Carax is making the point that people’s real identity is only shaped through connections with one another.

An alternate meaning behind the film can also be read if you begin to deconstruct each and every one of the eight short stories. In doing so, you will discover that Holy Motors is in fact a satirical attack on the arts but more importantly on film. It’s not a coincidence that the main character is named Oscar when he’s not “performing” for the pleasure of others; alluding to the coveted Academy Award statue. It’s also not a coincidence that towards the end of the film a character comes up to Oscar – now being his normal self walking around the streets at night – asking, “Where have you been? I didn’t know you were still doing this. I didn’t know you were still relevant.” Carax has delivered a film that spotlights what is currently popular in today’s Hollywood system while urging the audience that’s watching his film to “open their eyes.” Nothing proves this more true than the opening sequence. Oscar walks into a crowded movie theater and discovers everyone sitting there with their eyes closed instead of watching the movie. Of course, the film they are choosing to ignore is a simple black and white film of a naked man in motion; something that would seem too dull by today’s standards. Some of the films that seem to inspire the general public and Oscar voters more than the black/white projection are the mini vignettes that encompass the rest of Holy Motors.

Let’s take a look at each of these segments. Things kick off with what I would deem as the “Hollywood actor ugging him/herself up for a role.” Lavant adorns an old lady visage complete with a hideous nose and old rags which would give Charlize Theron in Monster some stiff competition for the Academy Award statue. Next, there is an elongated sequence that shows Lavant portraying an actor giving form to a CGI creature through the use of a motion capture suit. When you’re not fascinated by the actor’s agility and movements in the suit, you may come to see a scathing critique of the ridiculousness of CGI films like Avatar when it’s revealed he is giving motion to a dragon like creature making love to another creature. The point of which is to show how disconnected the human element is to the character due to the prominence of technology in film. The third segment seems both inspired by the Fellini idea of being obsessed with odd faces -the Italian Maestro frequently discussed how he cast his films based on a person’s face alone – and a Beauty and the Beast love story. An overhead shot of a Parisian cemetery sets the stage for an underground sewer dweller (Savant again) terrorizing the locals to the theme from Toho’s Godzilla. Eva Mendes is a model who is being photographed by a stereotypical director when the horrific man-creature shambles on to their shoot. While the director is fascinated by the hairy, dirty, and grotesque appearance of the homeless man, Mendes is both timid and yet sympathetic. The culmination of their love story is both intriguingly bizarre but appears to take a cue from the visual style of Renaissance artwork.

The film continues with a number of other slightly weaker vignettes that may not be as strong as the first three but still carry a weight that can be open to interpretation. We have a melodramatic sequence between a father and a daughter getting in a fight after he picks her up from a party. The reasoning that ignites the fight is so incredibly mundane and silly that you can’t help but attribute it to film’s depicting family drama. You also have a tale of a hitman which again results in a comedic and absurd finale. Then you have a dying man who in his last breaths looks to be passing on the family’s inheritance to his daughter at his side. This sequence is one of the few that actually hints at the possibility everyone acts or plays a part in this alternate reality; not just Lavant’s character Oscar. By the end of it, a couple of sequences follow that leave you feeling that the film is taking itself too serious. However, this is quickly relinquished with a closing bit that reminds the viewer that not only is this a comedic world where everyone and EVERYTHING is playing a part, but that you have just watched a film that will just as quickly divide cinephiles as unite them.

Carax has been extremely outspoken for his dislike of digital filmmaking; something he has said he was forced to shoot with for this film due to the producer’s budget restraints. This love/hate relationship he has regarding the medium plays out in full force here. Holy Motors combines several styles and film genres to serve as a commentary on the state of current cinema and society. The roles of individuals in society are examined in a way that parallel the function of cinema; blurring the idea of whether art imitates life or vice versa. At times Carax seems to point out the absurdity and pointless nature of it all, but he also seems to show how both people and film can serve others in a beneficial way and give relief when needed the most. Indeed, there is a function for us all and for all types of films regardless if they come across as meaningless. Maybe the opening sequence of the audience watching with their eyes closed isn’t them rejecting the banality of the “overly-simple” black and white image of the naked man basically doing nothing. In fact, maybe it shows an audience who is using their minds instead of their eyes and imagining a film (or life) that is more unique and enjoyable than anything that can be put on screen. Documenting our lives in a reality TV show fashion as we “act” for the amusement of others isn’t enough anymore as Oscar begins to accept by the finale of the film. We have become bored and docile in our roles as the entertainer of others. Life itself and maybe even film aren’t enough of an escape for us. If that is the case, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was wrong about “life being stranger than the mind.” To go down this path even further would give way to a discussion that would diverge even more from the main focus: Carax’s film. One thing I do know is in fact that Holy Motors is one of the strangest films I have ever seen in my life and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I look forward to studying and unfolding the many layers of Leos Carax’s bizarre fable about cinema and life for years to come.