Comic Review: ‘SNOWPIERCER – VOL 1: THE ESCAPE’

So the artist of the SNOWPIERCER graphic novel (GN), upon which the upcoming Bong Joon-Ho film ‘Snowpiercer’ is based, says if he was going to adapt any science-fiction novel to a comic, he’d choose Philip K Dick’s ‘UBIK’. Which is a really, really awesome novel to pick because it’s one of his most underrated books (compared to ‘Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?’) as well as probably his most frightening. The two guys behind the SNOWPIERCER GN are French, and belong to that most elusive and rarified class of creatives, the comic book artist. Well, at least in France, they tend to be more of the black sheep than they are here, though even in American comic book culture, the artists themselves are often considered secondary.

What sets French comic book artists (like the legendary Mœbius or the similarly mononymous Tardi) apart is their tendency to eschew easy genre work for literary minded stories that don’t sit comfortably next to superheroes or other “pulp” material. When a French cartoonist DOES create something more genre-friendly, it’s usually something ambitious or groundbreaking, because dammit, the French are Laissez-faire about everything but art. Thus, SNOWPIERCER.

But before I start breaking down SNOWPIERCER into digestible components suitable for your amusement, let me digress for a moment and discuss the context of the film. First off, it’s actually a partnership between Bong Joon-ho and long-time friend Chan-wook Park, who produced the film. Both got their starts with, surprise, genre films: Joon-ho had his ‘Jaws’-by-way-of-Korea creature feature ‘The Host’ and Park is best known for the transgressive thriller ‘Oldboy’. Both, naturally, had aspirations beyond their humble roots, and while both have forged distinguished careers alongside each other, their arcs have been identical: they’ve grown away from the fantastic and narrowed their focus on the more intimate kind of horror, often splashed with their distinctive Korean humor.

Joon-ho, in particular, had an incredible exploration of the darker side of motherhood with ‘Madeo (Mother)’ that could certainly be classified as a mystery thriller but dedicated most of its runtime to fleshing out the dysfunction and eccentricity of small-town South Korea. It’s a film that’s got a nearly perfect critical appraisal yet, outside foreign film aficionados, has never found an audience. Released around the same time, Park’s ‘Bakjwi (Thirst)’ drained vampire horror of its gore and turned out a quirky mix of comedy and horror, well-received by critics and, thanks to its easily-categorization (vampire flick), seen by more than a few people in the US market. But his attempt to capitalize on that with his first English-language film, ‘Stoker’, didn’t do nearly as well, thanks mainly to what critics saw as a tedious Hitchcock fetish, compounded by the absence of any identifiable genre trappings as well as a lack of any real shock value, expected by this point from the creator of ‘Lady Vengeance’ and ‘‘Bakjwi’.

So, having seen their more eclectic offerings suffer the apathy of indifferent markets outside Korea, ‘Snowpiercer’ makes a lot more sense. As a graphic novel, despite having been written in the ‘80s, it fits into the dwindling but relevant post-apocalyptic social dystopia trend (‘The Road’ or, if you prefer, ‘The Hunger Games’) but still manages to not only stand for more than just grim titillation but evokes some of the best classic literature in history, which I will discuss presently. In this way, Park and Joon-ho have wisely invested into a narrative that populist critics can embrace as an archetypal tail, literary critics can analyse deeply into the settings innovative details and the general population can generally be shocked/awed by. Think of ‘Titanic’ meets ‘The Hunger Games’ and you’ve got an idea of what sort of basic appeal this story has. What worries me, though, is that these are two directors whose films have been very quirky, intimate and absorbing. That’s what I love about them. There’s nothing personal about SNOWPIERCER though. It’s very much a tale of humanity, and I hope these two filmmakers don’t abandon the color and character of their signature films in favor of the kind of bleak grandeur everybody’s selling nowadays.

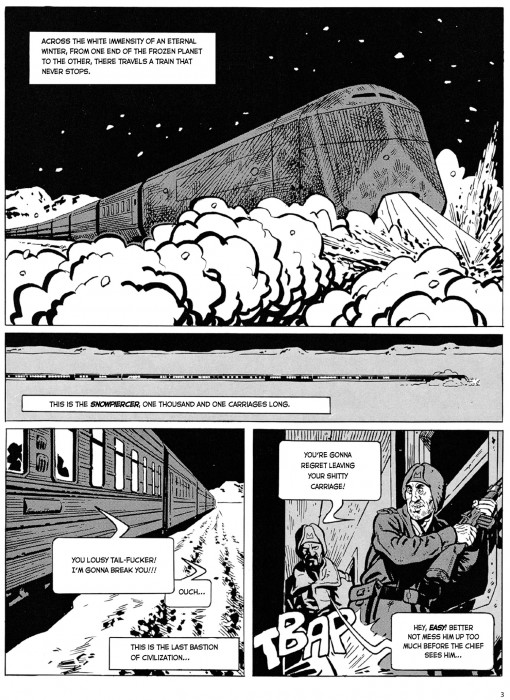

“Bleak grandeur” certainly is the most apt description of SNOWPIERCER I can come up with, given a need for brevity. The several pages that open the book are punctuated with panels that look out upon the eponymous train from the perspectives of wasteland ruminators listlessly observing the massive transport passing by. The train itself is both oppressive and animated, the engine vaporizing ice from the tracks with a compressed beam of nuclear fire spewing from its unsmiling mouth at the bottom of a long, dismal face upon which two narrow, passionless eyes look ahead dispassionately. These brief moments of context drop off a bit as the protagonists are introduced but once their journey to the head of the train begins, we occasionally return to the outside world long enough to be reminded, necessarily, of the world (or lack thereof) outside, as well as the seeming omnipotence of the Snowpiercer. Still, artistically, those shots are some of the most impressive exercises of Jean-Marc Rochette’s illustrative talents, their stark black-white contrasts only gaining in sublime dread as the narrative grows in stakes. Those moments are probably what I’m most eager to see in the film, despite the story that takes place entirely within the Snowpiercer itself.

The story is truly one of the boldest, most instinctively authentic things I’ve read in a long time. I can’t imagine what the actual roots of the ideas it’s built on come from, but I can certainly talk about the stuff that seems to have the strongest connection to it. One of the first things I thought of as I read it was Mark Twain’s short story ‘Cannibalism In The Cars’, in that it created allegory out of starving masses trapped on a train in a freezing wasteland, though Twain’s aim was satire rather than drama. If anything, comparing the two demeans SNOWPIERCER, as its broad, epic scope idealizes the allegory, rather than ruthlessly mocking a narrower spectrum of humanity that, in the end, becomes the targets of Jacques Lob & Rochette’s aims anyway.

But while Twain was cutting with his typically succinct razor-like satire, the SNOWPIERCER duo prop up their lofty themes with some impressively heavy world-building. They establish a gripping procedural flow to the unfolding events, the whole episode taking place in a breakneck 48 hours that feels like weeks. Their clever hook of having forcing their protagonists to travel through each car on their way to the engine provides ample opportunity to elaborate on their train-as-society conceit; we see how farming becomes a chore, how food production turns into faceless manufacturing, how bureaucracy works against even those who obey it to the letter, etc. There are moments of Kafka-esque surreality to how dysfunctional it all is, especially nearer the upper-class cars. Despite basically being human trash to them, the bottom-caste protagonist is, at one point, childishly prodded for answers to inane questions posed by ignoble yet powerful authority figures, not long after he’s had his head shaved. It also goes without saying that Orwell and Huxley, those omnipresent bastards of dystopian fiction, figure prominently in SNOWPIERCER’s fictive DNA, particularly in the more cynical explorations of how the freedom of the upper class has created a warped kind of nihilism, isolated from the suffering of the middle and lower classes, or “tail-fuckers” as they’re so derisively labeled by basically everyone. So, yeah, this story might have a bit of a socialist bent.

The visuals, all very precise, molded, unfiltered depictions of lots of Europeans with angry mugs and unregulated facial hair, enforce the dreariness of it all. Occasionally there’s a slight change of scenery and there are multiple action scenes that are, despite the suffocating oppression, quite thrilling. And when they slip in some unusual notes of actual science fiction (such as the “Mama” car or the engine room) it’s brief but enthralling stuff. This really is a graphic novel that needed to be made into a movie, before anything else though. So much of it is just talking head exposition that, if not for Rochette’s consistently engrossing visual drama, it would collapse under the weight of its own density.

What’s also intriguing, to a certain extent, about SNOWPIERCER, is its parallels to the archetypal “Ark” myth, a story which is also getting a similarly gritty reimagining courtesy director Darren Aronofsky, whose last epic ‘The Fountain’ was ALSO based off a graphic novel, though said graphic novel was, in fact, based off the rejected script for the film. Anyway, like the Ark concept, SNOWPIERCER sees a world obliterated as punishment for humanity’s sins and the subsequent desperate clinging to a vessel specifically designed as a safeguard for the survival of human life, nomadically marching through the remnants, waiting for some sign of hope. Except that SNOWPIERCER’s creators twisted that concept into an intensely cruel attack on humankind’s inherent fallibility, depending on your outlook, realistically/unfairly painting the whole of our kind as incapable of saving itself, serving only the interests of greed and egotism. As a cautionary tale, SNOWPIERCER is not only annoyingly redundant but petulantly incessant.

SNOWPIERCER represents both an attempt to evoke the contemplative, haunting, realistic nightmares of classic dystopian literature while utilizing a novel setting to present a wealth of ideas, all of which serve to bolster the theme of the potential and likely self-destruction of humankind. When the graphic novel debuted back in the ‘80s, stories like this one were still fresh and confrontative (see ‘THX 1138’, which SNOWPIERCER also lifts from). But given the current climate of exploitative bleakness (‘The Hunger Games’, ‘The Walking Dead’, ‘REVOLUTION’, etc), it’s hard to be impressed by its monotonous, if ambitious, intensity. It also seems rather backwards to depict the ultimate failure of humankind so pessimistically while so passionately trying to get said audience to invest in your story to begin with. Bit of a masochistic affair, really.